Original post: https://yunpengn.github.io/blog/2019/05/04/consistent-redis-sql/

Nowadays, Redis has become one of the most popular cache solution in the Internet industry. Although relational database systems (SQL) bring many awesome properties such as ACID, the performance of the database would degrade under high load in order to maintain these properties.

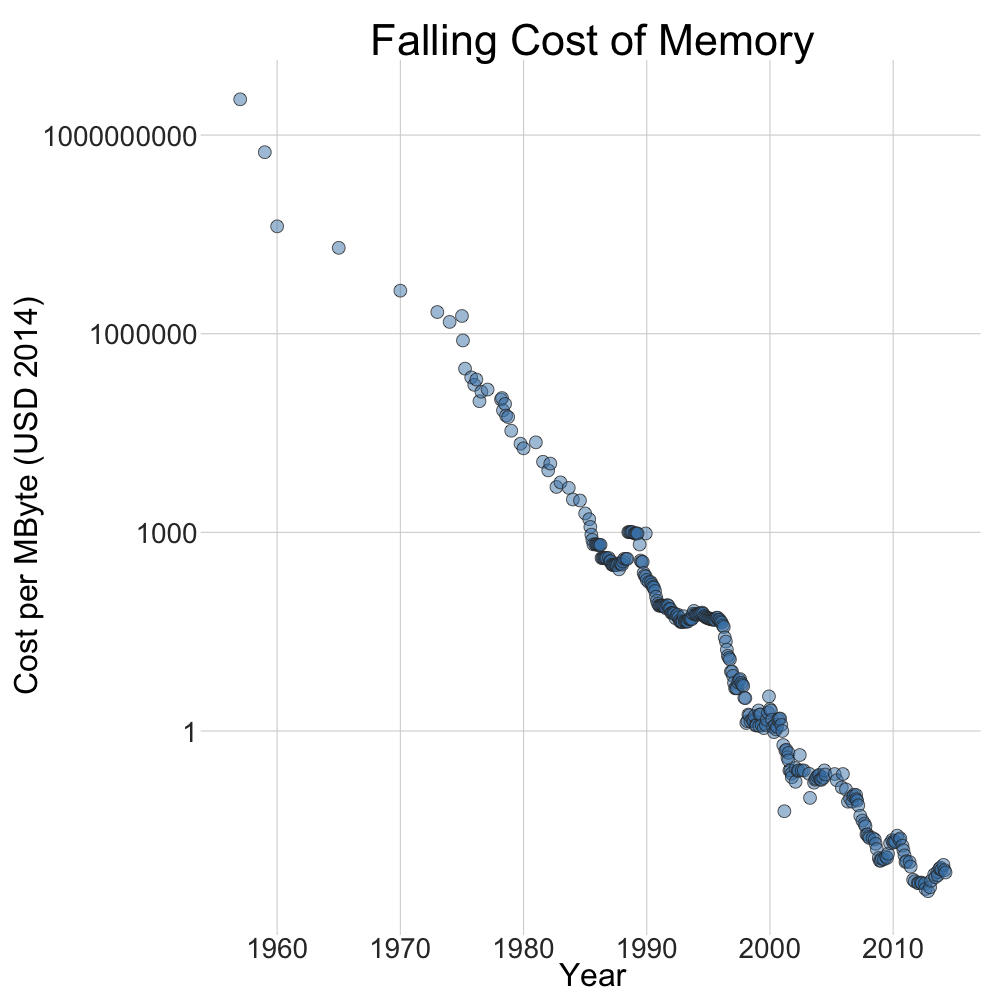

In order to fix this problem, many companies & websites have decided to add a cache layer between the application layer (i.e., the backend code which handles the business logic) and the storage layer (i.e., the SQL database). This cache layer is usually implemented using an in-memory cache. This is because, as stated in many textbooks, the performance bottleneck of traditional SQL databases is usually I/O to secondary storage (i.e., the hard disk). As the price of main memory (RAM) has gone down in the past decade, it is now feasible to store (at least part of) the data in main memory to improve performance. One popular choice is Redis.

Certainly, most systems would only store the so-called “hot data” in the cache layer (i.e., main memory). This is according to the Pareto Principle (also known as 80/20 rule), for many events, roughly 80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes. To be cost-efficient, we just need to store that 20% in the cache layer. To identify the “hot data”, we could specify an eviction policy (such as LFU or LRU) to determine which data to expire.

Background

As mentioned earlier, part of the data from the SQL database would be stored in in-memory cache such as Redis. Even though the performance is improved, this approach brings a huge headache that we do not have a single source of truth anymore. Now, the same piece of data would be stored in two places. How can we ensure the consistency between the data stored in Redis and the data stored in SQL database?

Below, we present a few common mistakes and point out what could go wrong. We also present a few solutions to this tricky problem.

Notice: to ease our discussion here, we take the example of Redis and traditional SQL database. However, please be aware the solutions presented in this post could be extended to other databases, or even the consistency between any two layers in the memory hierarchy.

Various Solutions

Below we describe a few approaches to this problem. Most of them are almost correct (but still wrong). In other words, they can guarantee consistency between the 2 layers 99.9% of the time. However, things could go wrong (such as dirty data in cache) under very high concurrency and huge traffic.

However, these almost correct solutions are heavily used in the industry and many companies have been using these approaches for years without major headache. Sometimes, going from 99.9% correctness to 100% correctness is too challenging. For real-world business, faster development lifecycle and shorter go-to-market timeline are probably more important.

Cache Expiry

Some naive solutions try to use cache expiry or retention policy to handle consistency between MySQL and Redis. Although it is a good practice in general to carefully set expiry time and retention policy for your Redis Cluster, this is a terrible solution to guarantee consistency. Let’s say your cache expiry time is 30 minutes. Are you sure you can undertake the danger of reading dirty data for up to half an hour?

What about setting the expiry time to be shorter? Let’s say we set it to be 1 minute. Unfortunately, we are talking about services with huge traffic and high concurrency here. 60 seconds may make us lose millions of dollars.

Hmm, let’s set it to be even shorter, what about 5 seconds? Well, you have indeed shortened the inconsistent period. However, you have defeated the original objective of using cache! You will have a lot of cache misses and likely the performance of the system will degrade a lot.

Cache Aside

The algorithm for cache aside pattern is:

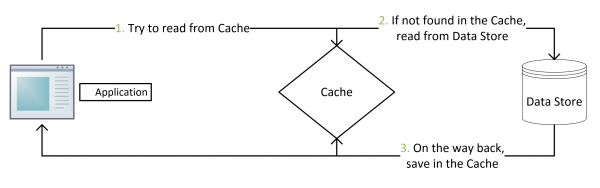

- For immutable operations (read):

- Cache hit: return data from Redis directly, with no query to MySQL;

- Cache miss: query MySQL to get the data (can use read replicas to improve performance), save the returned data to Redis, return the result to client.

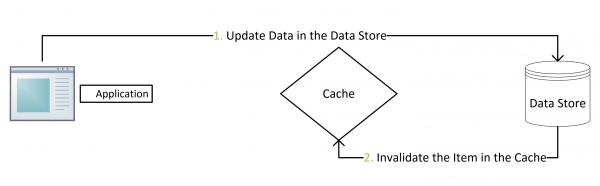

- For mutable operations (create, update, delete):

- Create, update or delete the data to MySQL;

- Delete the entry in Redis (always delete rather than update the cache, the new value will be inserted when next cache miss).

This approach would mostly work for common use cases. In fact, cache aside is the de facto standard for implementing consistency between MySQL and Redis. The famous paper, Scaling Memecache at Facebook also described such an approach. However, there does exist some problems with this approach as well:

- Under normal scenarios (let’s say we assume the process is never killed and write to MySQL/Redis will never fail), it can mostly guarantee eventual consistency. Let’s say process

Atries to update an existing value. At a certain moment,Ahas successfully updated the value in MySQL. Before it deletes the entry in Redis, another processBtries to read the same value.Bwill then get a cache hit (because the entry has not been deleted in Redis yet). Therefore,Bwill read the outdated value. However, the old entry in Redis will eventually be deleted and other processes will eventually get the updated value. - Under extreme situations, it cannot guarantee eventual consistency as well. Let’s consider the same scenario. If process

Ais killed before it attempts to delete the entry in Redis, that old entry will never be deleted. Hence, all other processes thereafter will keep reading the old value. - Even under normal scenarios, there exists a corner case with very low probability where eventual consistency may break. Let’s say process

Ctries to read a value and gets a cache miss. ThenCqueries MySQL and gets the returned result. Suddenly,Csomehow is stuck and paused by the OS for a while. At this moment, another processDtries to update the same value.Dupdates MySQL and has deleted the entry in Redis. After that,Cresumes and saves its query result into Redis. Hence,Csaves the old value into Redis and all subsequent processes will read dirty data. This may sound scary, but its probability is very low because:- If

Dis trying to update an existing value, this entry by right should exist in Redis whenCtries to read it. This scenario will not happen ifCgets a cache hit. In order for such a case to happen, that entry must have expired and been deleted from Redis. However, if this entry is “very hot” (i.e., there is huge read traffic on it), it should have been saved into Redis again very soon after it is expired. If this belongs to “cold data”, there should be low consistency on it and thus it is rare to have one read request and one update request on this entry simultaneously. - Mostly, writing to Redis should be much faster than writing to MySQL. In reality,

C‘s write operation on Redis should happen much earlier thanD‘s delete operation on Redis.

- If

Cache Aside – Variant 1

The algorithm for the 1st variant of cache aside pattern is:

- For immutable operations (read):

- Cache hit: return data from Redis directly, with no query to MySQL;

- Cache miss: query MySQL to get the data (can use read replicas to improve performance), save the returned data to Redis, return the result to client.

- For mutable operations (create, update, delete):

- Delete the entry in Redis;

- Create, update or delete the data to MySQL.

This can be a very bad solution. Let’s say process A tries to update an existing value. At a certain moment, A has successfully deleted the entry in Redis. Before A updates the value in MySQL, process B attempts to read the same value and gets a cache miss. Then, B queries MySQL and saves the returned data to Redis. Notice the data in MySQl has not been updated at this moment yet. Since A will not delete the Redis entry again later, the old value will remain in Redis and all subsequent reads to this value will be wrong.

According to the analysis above, assuming extreme conditions will not happen, both the origin cache aside algorithm and its variant 1 cannot guarantee eventual consistency in some cases (we call such cases the unhappy path). However, the probability of the unhappy path for variant 1 is much higher than that of the original algorithm.

Cache Aside – Variant 2

The algorithm for the 2nd variant of cache aside pattern is:

- For immutable operations (read):

- Cache hit: return data from Redis directly, with no query to MySQL;

- Cache miss: query MySQL to get the data (can use read replicas to improve performance), save the returned data to Redis, return the result to client.

- For mutable operations (create, update, delete):

- Create, update or delete the data to MySQL;

- Create, update or delete the entry in Redis.

This is a bad solution as well. Let’s say there are two processes A and B both attempting to update an existing value. A updates MySQL before B; however, B updates the Redis entry before A. Eventually, the value in MySQL is updated by B; however, the value in Redis is updated by A. This would cause inconsistency.

Similarly, the probability of unhappy path for variant 2 is much higher than that of the original approach.

Read Through

The algorithm for read through pattern is:

- For immutable operations (read):

- Client will always simply read from cache. Either cache hit or cache miss is transparent to the client. If it is a cache miss, the cache should have the ability to automatically fetch from the database.

- For mutable operations (create, update, delete):

- This strategy does not handle mutable operations. It should be combined with write through (or write behind) pattern.

A key drawback of read through pattern is that many cache layers may not support it. For example, Redis would not be able to fetch from MySQL automatically (unless you write a plugin for Redis).

Write Through

The algorithm for write through pattern is:

- For immutable operations (read):

- This strategy does not handle immutable operations. It should be combined with read through pattern.

- For mutable operations (create, update, delete):

- The client only needs to create, update or delete the entry in Redis. The cache layer has to atomically synchronize this change to MySQL.

The drawbacks of write through pattern are obvious as well. First, many cache layers would not natively support this. Second, Redis is a cache rather than an RDBMS. It is not designed to be resilient. Thus, changes may be lost before they are replicated to MySQL. Even if Redis has now supported persistence techniques such as RDB and AOF, this approach is still not recommended.

Write Behind

The algorithm for write behind pattern is:

- For immutable operations (read):

- This strategy does not handle immutable operations. It should be combined with read through pattern.

- For mutable operations (create, update, delete):

- The client only needs to create, update or delete the entry in Redis. The cache layer saves the change into a message queue and returns success to the client. The change is replicated to MySQL asynchronously and may happen after Redis sends success response to the client.

Write behind pattern is different from write through because it replicates the changes to MySQL asynchronously. It improves the throughput because the client does not have to wait for the replication to happen. A message queue with high durability could be a possible implementation. Redis stream (supported since Redis 5.0) could be a good option. To further improve the performance, it is possible to combine the changes and update MySQL in batch (to save the number of queries).

The drawbacks of write behind pattern are similar. First, many cache layers do not natively support this. Second, the message queue used must be FIFO (first in first out). Otherwise, the updates to MySQL may be out of order and thus the eventual result may be incorrect.

Double Delete

The algorithm for double delete pattern is:

- For immutable operations (read):

- Cache hit: return data from Redis directly, with no query to MySQL;

- Cache miss: query MySQL to get the data (can use read replicas to improve performance), save the returned data to Redis, return the result to client.

- For mutable operations (create, update, delete):

- Delete the entry in Redis;

- Create, update or delete the data to MySQL;

- Sleep for a while (such as 500ms);

- Delete the entry in Redis again.

This approach combines the original cache aside algorithm and its 1st variant. Since it is an improvement based on the original cache aside approach, we can declare that it mostly guarantees eventual consistency under normal scenarios. It has attempted to fix the unhappy path of both approaches as well.

By pausing the process for 500ms, the algorithm assumes all concurrent read processes have saved the old value into Redis and thus the 2nd delete operation on Redis will clear all dirty data. Although there does still exist a corner case where this algorithm to break eventual consistency, the probability of that would be negligible.

Write Behind – Variant

In the end, we present a novel approach introduced by the canal project developed by Alibaba Group from China.

This new method can be considered as a variant of the write behind algorithm. However, it performs replication in the other direction. Rather than replicating changes from Redis to MySQL, it subscribes to the binlog of MySQL and replicates it to Redis. This provides much better durability and consistency than the original algorithm. Since binlog is part of the RDMS technology, we can assume it is durable and resilient under disaster. Such an architecture is also quite mature as it has been used to replicate changes between MySQL master and slaves.

Conclusion

In conclusion, none of the approaches above can guarantee strong consistency. Strong consistency may not be a realistic requirement for the consistency between Redis and MySQL as well. To guarantee strong consistency, we have to implement ACID on all operations. Doing so will degrade the performance of the cache layer, which will defeat our objectives of using Redis cache.

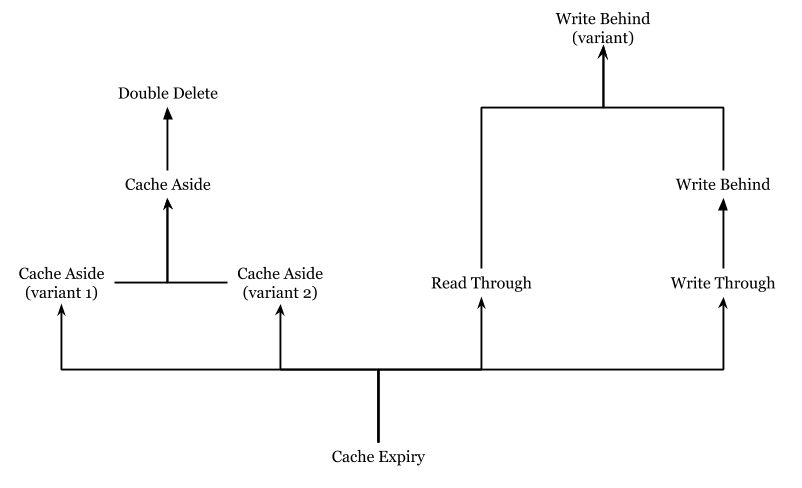

However, all the approaches above have attempted to achieve eventual consistency, of which the last one (introduced by canal) being the best. Some of the algorithms above are improvements to some others. To describe their hierarchy, the following tree diagram is drawn. In the diagram, each node would in general achieve better consistency that its children (if any).

We conclude there would always be a tradeoff between 100% correctness and performance. Sometimes, 99.9% correctness is already enough for real-world use cases. In future researches, we remind that people should remember to not defeat the original objectives of the topic. For example, we cannot sacrifice performance when discussing the consistency between MySQL and Redis.